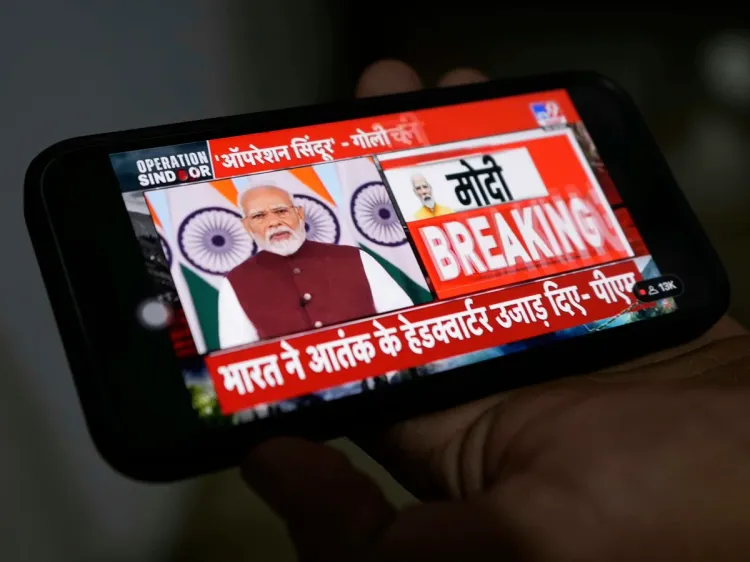

Bangladesh’s Tilt Toward Pakistan Isn’t Just Diplomacy - It’s a Reckoning

What we’re witnessing in Dhaka isn’t a subtle diplomatic thaw—it’s a geopolitical pivot with decades of weight behind it. For the first time since the bloody rupture of 1971, Bangladesh is actively reimagining Pakistan not as a historical adversary but as a viable strategic partner. And it's doing so loudly, unapologetically, and—some would argue—recklessly.

The architects of this shift? An interim government led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, who stepped in after Sheikh Hasina’s abrupt fall from power last year amid mass protests and rising authoritarian backlash. Under Yunus’s stewardship, Bangladesh is making moves that would’ve been unthinkable just months ago.

“There are certain hurdles we need to overcome, but we must find ways to move forward,” Yunus told Pakistan’s Foreign Secretary Amna Baloch during her April visit to Dhaka.

Pakistan, long diplomatically cornered in South Asia, has seized the opening with surprising deftness. Foreign Office spokesperson Mumtaz Zahra Baloch spoke of Islamabad’s readiness for “robust, multifaceted” ties “to enhance peace in the region.” Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif echoed the optimism in an Eid call with Yunus, pointing to a “positive momentum in bilateral relations … particularly in trade and travel.”

And that “momentum” is real. Government-to-government trade has resumed. Bangladesh just imported 50,000 tonnes of Pakistani rice. A Pakistani cargo vessel docked in Chittagong this year—the first direct shipment in decades. Pakistan even waived visa fees for thousands of Bangladeshi travelers, a gesture Dhaka reciprocated.

But this isn’t just about trade. Behind the headlines is a quiet, coordinated security realignment. Military brass are on the move. Pakistan’s ISI chief flew to Dhaka for intelligence talks. Bangladesh’s top general returned the visit. Joint naval drills are under discussion. There’s talk of Dhaka exploring JF-17 fighter jet purchases from the Pakistan-China consortium.

What changed?

Simply put: India.

Yunus is playing a long game—and that means stepping back from the suffocating embrace of New Delhi. In the words of the interim leader himself, “Bangladesh wanted good ties with India, but something always went wrong.”

That “something” isn’t hard to identify: India’s reluctance to accommodate Bangladesh’s strategic autonomy, its backing of Hasina during protests, and its punitive visa and trade freeze after the regime change. To many in Dhaka, New Delhi increasingly looks like a patron, not a partner.

Which is precisely why Yunus is doubling down on regional multipolarity, championing a revival of SAARC—South Asia’s dormant regional bloc. “I want a summit of SAARC leaders … even if it is only for a photo session,” he said recently. Shehbaz Sharif, predictably, was happy to oblige.

But let’s be clear: this new friendship comes with baggage.

Bangladesh continues to demand a formal apology and $4.5 billion in reparations for the 1971 genocide. “Unsettled issues … need to be resolved for a solid foundation,” Foreign Secretary Jashim Uddin rightly reminded his Pakistani counterparts.

And at home, the interim government’s decisions raise red flags. The rehabilitation of Jamaat-e-Islami, a party tied to 1971 atrocities, sends a dangerous signal. Critics argue the pivot to Pakistan is empowering Islamist factions once pushed to the margins. A recent Indian intelligence warning alleged that “ISI’s network … [is] weaponising groups for spreading terror.” One need not fully endorse that view to see the risks of soft-pedaling on religious extremism.

Economically, this realignment still lacks heft. Trade with Pakistan barely scratches $800 million—India’s figure is over $13 billion. But geopolitics isn’t always about balance sheets. It’s about leverage, optics, and autonomy.

Bangladesh is using this moment to reset its regional identity. Whether it succeeds depends on how much of this détente is real, and how much is symbolic. It also depends on the outcome of national elections due later this year.

If a newly elected government reaffirms this course, South Asia might just witness the beginnings of an unlikely alliance: two estranged siblings, once ripped apart by war, now quietly rebuilding what politics destroyed.

But if not—if Yunus’s efforts collapse under the weight of history and domestic backlash—then this will be remembered not as a pivot, but as a pause.

Fatima Hassan is a freelance journalist and the co-founder & Multimedia Editor of Echoes Media, dedicated to crafting impactful stories that resonate with diverse audiences. A journalism graduate of Northwestern University, Fatima combines analytical rigor with creative storytelling to explore complex issues and amplify unheard voices.

Member discussion