Climate-induced disasters are isolating Pakistan’s women

From a young age, 28-year-old Khanzadi Kapri, from Sindh’s Mirpurkhas district’s Juddho Tehsil, has witnessed floods and the devastation they bring. “I was 13 years old when the 2011 floods hit,” she recalls. Between mid-August and early September 2011, Sindh and five districts of Balochistan experienced heavy monsoon rains and flooding that affected approximately 5.8 million people. Mirpurkhas was among the worst-hit areas. Kapri still remembers the destruction that followed and how she struggled to manage her health and hygiene.

Recurring trauma

Eleven years later, Kapri once again found herself in the same situation when the 2022 superfloods struck. This time, the losses were even more personal; she lost her father and sister, who passed away during labour pains. Kapri experienced a layered trauma: she watched her community being destroyed while simultaneously facing her own grief.

“We had to bury my father and sister in inundated graveyards,” she says. “Even now, when I think back, it feels as if it’s all happening in this moment.”

The 2022 floods primarily affected rural and underdeveloped regions of the country, affecting nearly 33 million people. As many as 8.2 million women of reproductive age were affected, along with over 1,460 health facilities, of which 432 were fully damaged and 1,028 were partially damaged. The catastrophe compounded women’s healthcare and hygiene issues.

In the absence of immediate government relief, flood victims were left to manage evacuation and rescue efforts themselves. “All our routes were cut off. We had to rescue people by tying charpoys (woven beds) together. The rescue officials came much later,” Kapri explained.

Despite her loss, Kapri pushed on and began working with various community and non-governmental organisations to help with relief and rehabilitation. “These young girls and women; they’re my own community. Of course, we have to help them,” she said. But flood relief shouldn’t have to depend on individuals like her. In a disaster of this scale, both provincial and federal disaster management authorities should have taken the lead, considering this has been a recurring event in every monsoon season.

Though she appeared resilient, Kapri mourned her lost loved ones while confronting the reality that her community had been left to fend for itself. A deep sense of isolation sets in when devastation like this happens.

The events of 2022 left Kapri deeply disturbed, compelling her to seek professional help on her own. Unfortunately, for her, the trauma continues to resurface as Pakistan experiences increasingly erratic and intense monsoon rains. “We experienced flooding in 2024 as well, but it wasn’t highlighted because the devastation wasn’t as widespread,” said Kapri.

This year again, several areas in Sindh are inundated following monsoon rains and India’s release of water into Pakistan. Kapri is once again involved in fundraising and providing relief support. She has effectively taken on the role of the state within her community, and while her work is extraordinary, it is not a burden she should bear alone.

While Kapri was able to recognise the need for professional support and seek it, many girls and women are unable to acknowledge or afford such interventions. They continue to carry the trauma, which affects their overall well-being in the long term. Mehwish Ashfaq, an associate clinical psychologist who worked with a group of flood-affected individuals in Sindh, shared that “most women treated mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and trauma as secondary concerns. They were more focused on immediate needs such as food and healthcare for their children.”

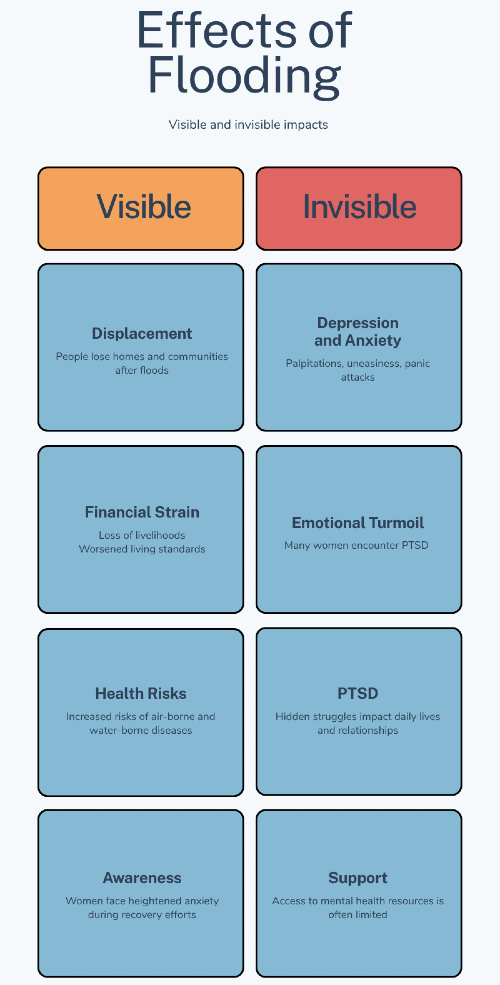

While it is natural for women, as primary caregivers, to prioritise shelter, food, and healthcare, the growing anxiety and trauma they experience threaten their overall wellbeing. In the absence of timely interventions, as is often the case, they are left struggling internally, caught in a persistent state of emotional turmoil.

Women’s health: An afterthought in disaster response

Approximately 62% of Pakistan’s population lives in rural areas, with women making up about half of that number. As of 2018, 75% of women and girls in the labour force were employed in the agricultural sector. Yet, both provincial and federal governments have not only excluded women from agricultural policies but have also failed to recognise their unique needs arising from climate change and environmental degradation. Disaster preparedness and rehabilitation frameworks do not address women’s issues either.

In rural and remote areas, the healthcare situation, particularly for women, is especially dire due to limited access. During disasters, men typically lead relief and rehabilitation efforts, further sidelining women, who often receive support only when female community workers step in.

Sana Nadeem, an associate clinical psychologist, says that women and girls facing displacement and climate disasters often suffer from inadequate access to sanitary products, nutritious food, and proper healthcare. “This leads to chronic fatigue, stress, and psychological distress, which can become long-term,” she added.

Dr Alia Haider, founder of Khalq Health Clinic and a climate activist, shared that girls and women in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s flood-hit Bajaur and Buner were affected by urinary tract infections (UTIs) and other health issues. Unfortunately, though, their healthcare was deemed secondary by the patriarchs of their community. It wasn’t until Haider’s team reached these areas that the women received the necessary support.

Haider informed us that most women in this region traditionally stay within their homes, but step out in their gardens or lawns to get some relief. “However, since the August floods, many have lost their homes and now live in camps, where they remain confined with no space for rest or recovery,” she added. Already reeling from the trauma of flooding and displacement, their frustration and distress are intensifying.

Among those affected are young girls and women left without male guardians. Many of these women, who had never interacted with anyone beyond their mahrams (close male relatives), are now suddenly forced to manage everything on their own. This abrupt shift has taken a severe toll on their mental and emotional health.

Nadeem says that, “The loss of male guardians and support networks in traditionally conservative communities further deepens women’s sense of insecurity, isolation, and dependence.” This lack of safety and access to necessities not only heightens anxiety and depression but also limits women’s ability to manage their daily needs. These intersecting challenges compound the physical, emotional, and social burdens women endure during crises.

Unsung frontline workers

22-year-old Adeeba Amin, a grassroots worker focusing on sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR) among women and co-founder of the Saviours Organisation, has worked across several areas of South Punjab, providing flood relief. Originally from Multan, Amin travelled to affected areas within and beyond the city, including Alipur and Sultanpur, visiting bastis and villages to distribute menstrual hygiene kits to women.

Although many assume that relief work does not leave emotional scars, Amin carries the grief of what she has witnessed – the destruction, loss, and countless stories of suffering she has heard firsthand. Adding to the injustice, her work does not receive any recognition. “I’m not getting paid for this; I’m doing this voluntarily,” says Amin. “In Pakistan, there is no recognition for this sort of work.” While people may support your work on social media, it rarely translates into tangible help or support in the offline space.

Amin has also had to take days off from her job to assist flood-affected communities. While her commitment is admirable, it has taken a toll on her own health. To cope, she turns to meditation and journaling.

Female grassroots and community organisers face a multidimensional challenge as they are not just witnessing destruction and loss first-hand, but they often are also affected by these issues.

Those coming from lesser-affected regions may struggle to reintegrate into society. Their inability to openly share their experiences and a lack of empathy from others around them result in a sense of isolation.

The toll of displacement

The 2022 floods displaced 8 million people, while the ongoing floods have displaced at least 2.5 million. This time, in flood-affected areas of South Punjab, men often stayed behind to protect their land while women moved to relief camps. Many of these women helped transport belongings, while others are now dealing with relief workers on their own. These are tasks they had never undertaken before.

Amin shared the story of a widow who broke down at a flood relief camp: “I don’t have a husband or a son. My house was washed away, and my relatives are only worried about themselves,” Amin recounted. The widow’s relatives had also lost their homes. The woman now finds herself struggling alone, with two young children to care for and no one to rely on.

It is a particularly challenging situation for women because Pakistan has a communal culture, where people rely on one another for even the smallest needs. This reliance is even stronger in rural and tribal communities, where women typically move and interact only within their own circles. The frequently occurring disasters are breaking entire communities and forcing migration, leaving women without support systems.

Harassment in flood camps

Displacement brings not just physical and emotional strain, but also exposes women to new forms of risk. Displaced girls and women are frequently faced with sexual harassment within relief camps, particularly those without male guardians. Marvi Latifi, federal secretary of the Women Democratic Front, shared that women living in flood relief camps in Sindh during the 2022 floods reported instances of harassment. Amin raised similar concerns when speaking of the current floods.

Similarly, women who are forced to resettle or migrate to new regions after disasters face heightened risks of sexual exploitation and trafficking. In unfamiliar environments, with no one to turn to, they navigate the constant fear of abuse and harassment alone. Many encounter such advances almost immediately upon resettlement and are unable to avoid or resist them.

Most women are unable to report such incidents due to shame, stigma, and the risk of abandonment. As a result, they are forced to endure abuse and trauma silently, deepening their sense of loneliness.

Emerging mental health crisis

Women in Pakistan have consistently been at the forefront of climate and environmental emergencies, from floods to heatwaves and droughts. In disaster-affected regions, conservative norms often prevent women from evacuating without male escorts, forcing them to stay behind and brave dangerous conditions alone.

During heatwaves, women continue working in extreme heat and confined conditions. While death and heat exhaustion are immediate risks, the long-term psychological toll often goes unnoticed. These experiences create a profound sense of isolation. In a patriarchal culture that sidelines women’s needs and voices, their struggles remain invisible, and their risk continues to grow.

While there is growing global recognition of the mental health impacts of disasters linked to climate change and environmental degradation, this understanding is largely absent in Pakistan. It stems from the stigmatisation of mental disorders. According to the WHO, 24 million people in the country require psychiatric assistance. Yet, most people either do not fully understand the implications of mental disorders or struggle to seek professional support due to fear of shame and stigma. Individuals with symptoms of such disorders are faced with bullying, shame, and exclusion. Particularly, in rural areas, people often resort to spiritual or faith healers to treat mental health concerns due to cultural traditions, low literacy levels, and limited access to inclusive healthcare.

The situation is even more complex for women, as gender stereotypes often silence or dismiss them as being overly emotional or complaining when they speak about their mental health.

Ashfaq explained that in rural areas, particularly for women, mental illnesses are frequently labelled as signs of being “too emotional” or “crazy.” She cited common phrases like “yeh har waqt roti rehti hai” [she’s always crying] or “yeh toh pagal hai” [she’s crazy]. Consequently, many women experiencing anxiety or depression choose not to share their struggles with others.

A 2013 study revealed that Pakistani women lost nearly 1.2 million total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) to depression, compared to men’s more than 495,000 DALYs in 2013. “Anxiety exhibited a similar gender divide with women in the country losing over 376,700 total DALYs to anxiety while men lost approximately 212,000 DALYs.” A report by Koohi Goth Women’s Hospital, referring to a 2023 report, stated that at least 60% of the women in rural areas experience mental health conditions.

In many ways, women’s worsening mental health is interlinked with exacerbating environmental and climate-related issues. Those in the worst-affected regions are increasingly facing a prolonged sense of isolation and abandonment. This not only increases the prevalence of conditions such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD but also raises the risk of suicide.

Unlike men, who can often release their frustrations through social interaction, women and girls confined to makeshift shelters or isolated rooms in relief camps lack similar spaces to share or process their experiences. Nadeem believes that this situation demands urgent intervention to reduce psychological distress among affected women and to equip them with the tools needed to manage their mental health effectively.

Women, who are among the worst affected by Pakistan’s escalating climate and environmental crises, often overlook their own needs, just as the country’s disaster response and society at large do. Climate-induced disasters are not going to stop; they will only become more frequent and intense. Amid this growing uncertainty, it is crucial not to abandon the women who sustain our communities and nurture future generations, but to support and empower them. Both Ashfaq and Nadeem stressed the urgent need for interventions that not only address women’s current challenges but also equip them with the tools to manage their mental health during future crises.

Ayesha Mirza is a journalist focusing on social justice, climate change, minority rights, and gender issues.

Member discussion