Judicial Violence: Baloch Families Between Loss and Criminalization

Seven years ago, when she was just sixteen, Saira Baloch walked into a police station in Khuzdar for the first time. At her mother’s side, she was there to file a report — an FIR — over the enforced disappearance of her two elder brothers, Asif and Rasheed. But the visit ended as so many do for families in Balochistan seeking justice. The station house officer refused to register the case, bluntly telling them that no FIR would be filed against state institutions.

They returned home defeated. For two and a half years, Saira and her family clung to the hope that Asif and Rasheed would walk through the door. But no one came. For two and a half years, Saira and her family waited for news. None came. In 2021, determined to break the silence, Saira travelled to Quetta and took the case to the Balochistan High Court (BHC) and a Joint Investigation Team (JIT).

“The court would hear me and pass orders that law enforcement agencies should appear,” Saira recalled. “But that has never happened.”

When someone disappears in Balochistan, most families take the first desperate step: they go to the police station, hoping to lodge a First Information Report (FIR). More often than not, that never happens. The disappearance goes unrecorded in police records as if it never happened. If a person has disappeared and no FIR is registered, it means there is no official record of their disappearance—legally, it’s as if they were never taken

In rare cases, when persistence forces the police to file a report, it is usually against na maloom afraad — unknown persons. That, too, becomes part of the problem.

When no progress follows, families pin their hopes on the courts and the JITs. Notices are issued, and law enforcement agencies are summoned. But the orders are rarely enforced.

Initially, the courts begin to follow up on such cases—hearings are held, and orders are issued, directing that the state institutions involved must appear before the court. But in reality, this rarely happens. These institutions never show up, and the case gets caught in a prolonged and frustrating legal process. Over time, many of these cases are sidelined due to the overwhelming backlog. Families, too, gradually lose hope—exhausted by the endless delays.

And so, for many families, protest becomes the final, fragile ray of hope, their last way of calling out for their disappeared loved ones, their last clamor for justice. They spend years on the streets, carrying their pain and distress, yet finding a measure of solace in knowing they have something left to cling to. But in recent months, even that fragile satisfaction has been stripped away. Families who once stood on the roadside demanding answers are now themselves facing anti-terror cases in courts. FIRs have been lodged in local police stations against those families who protest.

Saira remembers the moment the courts failed her, and protest became her only path. In 2021, she joined a sit-in in Islamabad’s Red Zone alongside other families. In 2022, she spent 50 days at a sit-in in Quetta’s Red Zone. In 2023, she joined a three-day camp in Islamabad, again demanding her brothers’ safe return. And from late 2023 into January 2024, she sat for three months in Islamabad, enduring the cold, waiting.

Surprisingly, in 2024, Saira was named in an FIR for a protest in Khuzdar. “I didn’t even participate in the protest they accused me of,” she said. Since then, she says, at least four more FIRs have been registered against her. “And I believe there are more that I don’t even know about yet,” she added. Saira’s arrest warrant was issued on 23rd April 2024, and currently, she is on bail. She must regularly appear before the court in her hometown, Khuzdar,Balochistan. Having recently completed her intermediate studies, she had hoped to start university in Quetta. But the constant legal battles have cast a shadow over those plans.

“This has affected my studies. Sometimes, two or three times a month, I have to travel from Quetta to Khuzdar just to prove my innocence in court. And when I’m back in Quetta, I have to be present at the High Court for my brothers’ case,” she said.

Saira’s brothers, Asif and Rasheed, disappeared on 31 August 2018. After nearly three years of waiting in silence, she began to join every protest she could — in Khuzdar, in Quetta, and later in Karachi and Islamabad. Wherever families gathered to demand the return of their loved ones, Saira was there.

Now, she has been named in multiple FIRs for allegedly disobeying the law, along with Rasheed’s wife and her elder sister. For over a year, all three have been making repeated court appearances in Khuzdar, caught in a cycle of legal proceedings that offers no resolution.

From fighting for her brothers, Saira now finds herself entangled in a struggle for her own freedom. “Justice has simply disappeared for us,” she said.

Similarly, Sammi Deen Mohammad’s struggle for her father’s safe return has now spanned for about 16 years, a fight that has drawn recognition both within Pakistan and internationally. But now, Sammi herself faces mounting pressure. She has been named in multiple FIRs, and on 25th March 2025, she was arrested. She was released a few days later.

Sammi was just a child when her father, Dr. Deen Mohammad, was forcibly disappeared from Ornach, Balochistan in 2009. According to her, the clinic where he was taken from was only two kilometers from the local police station. The next day, when the family rushed to register an FIR, the police refused.

Sammi, too, is out on bail. She believes the state aims to keep human rights violations in Balochistan hidden from view. “If these abuses come to the surface, it would raise questions for the state,” she said. “Enforced disappearance is a major issue in Balochistan. No matter what they do, it cannot be hidden.”

According to Sammi, many families are threatened into silence and fear speaking out.

“That’s why so many never appear at protests,” Sammi said. “And for those who do, they face baton charges, shelling. They’re labelled as agents, told their loved ones aren’t missing but militants. And if that’s not enough, they’re hit with FIRs — to exhaust them, to force them to give up their struggle.”

Like Saira and Sammi, 17-year-old Mahzaib Baloch has found herself pulled into the same cycle of repression. It was the day of her final first-year intermediate exam at Hub Chowki on 19th May 2025. Mahzaib was seated in the exam hall when a lady constable entered and asked for her by name. The teacher told the constable to wait until the paper was over, but within moments, word spread that police had surrounded the hall.

After finishing her exam, Mahzaib, amid the crowd of students, managed to slip away. Later, she arranged for bail — and now, like so many others, she is out on bail, facing the weight of the charges against her.

Mahzaib’s paternal uncle has been missing since 2018, when she was just 12 years old. Since then, she has never left her grandmother, the mother of the disappeared Rashid Hussain, to stand alone. At every camp, every protest, Mahzaib has been there. That solidarity has come at a cost. She now has fourteen FIRs registered against her. On 27th March 2025, Mahzaib was arrested by the Hub police. She was released the following day.

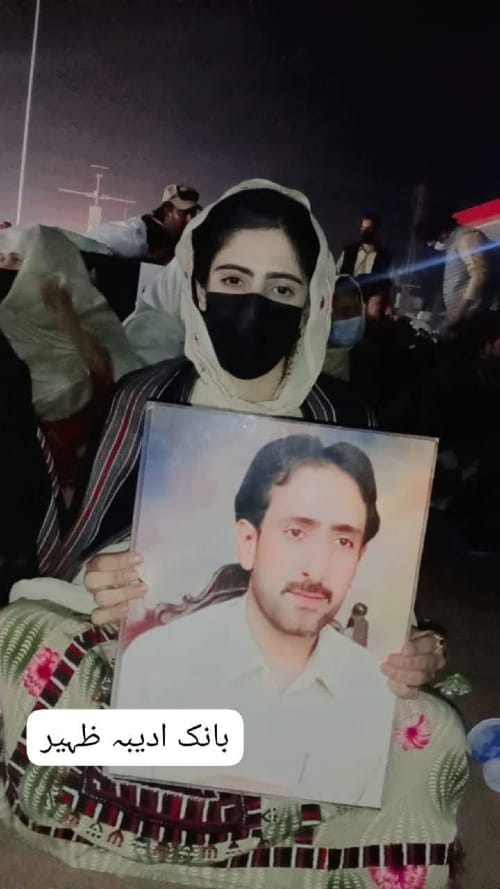

The story is no different for 21-year-old Adeeba Baloch, a resident of Panjgur and the daughter of Zaheer Baloch, who was forcibly disappeared in April 2015. Zaheer had been travelling when security forces took him at Hub Chowki. Zaheer’s brother rushed to the local police station to file an FIR, but, as so often happens, the police refused.

For two years, Adeeba and her family waited for answers. When none came, they turned to the only path left: protest. Since then, Adeeba has stood alongside other families demanding the release of the disappeared, even travelling to Islamabad in 2023. But like so many others, she has found no trace of her father.

Adeeba now faces an FIR for protesting in Panjgur.

“We have followed all legal channels as per Pakistan’s constitution — from FIR to JIT — but as victims, we are being made victims again,” she said. “Even after the JIT meetings, my family was pressured. And for the past two years, even the JIT hasn’t called us. How are we not supposed to protest? How can we just leave our father like that?”

(Note: just two days after recording comments from Adeeba for this piece, and from Zeeshan himself about the details of his father’s disappearance, Zeeshan was tragically killed. He disappeared on 29th June 2025, just after playing what would be his final football match, and his body was found the next day, on 30th June 2025. Following his disappearance that very night, his sister Adeeba staged a sit-in protest at Panjgur’s China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) road; she ended the sit-in after receiving her brother’s bullet-riddled body).

According to human rights lawyer Imaan Mazari, what these families are facing is part of a broader pattern of targeted repression. “First, your loved one is denied protection under the law, denied the right to a fair trial. They are taken outside the law’s safeguards. Then, when you seek legal remedies, you and your entire family — even those who may not be petitioners in court also face reprisals,” she said.

Mazari noted that this practice, once concentrated in Balochistan, is now spreading to Islamabad and Punjab. “The aim of these reprisals isn’t just to punish families for reporting, speaking out, or protesting. It’s to deter them from seeking justice in the first place. Because when you’re consumed with securing your bail or fighting fabricated anti-terror charges, you’re left with fewer resources and less strength to fight for your disappeared loved ones.”

In 2018, a video filmed outside the Quetta Secretariat went viral across social media, where families tried to protest near the Balochistan Governor House, which showed Seema Baloch, a mother of four and the sister of Shabir Baloch, who has been missing since 4th October 2016. In the footage, Seema is in tears, her voice breaking as she screams at the police who had blocked their route and threatened the protesters with baton charges and arrest. Beside her stands Shabir’s wife, Zareena, silently weeping.

“You have already taken my brother, and now you won’t even let us protest for him?” Seema cried, her words choked by sobs.

Like so many others, Seema’s search for justice followed the familiar path: an FIR initially refused. The courts and the JIT could not bring her brother back. Yet Seema never abandoned her struggle. Since 2016, she has been a constant figure at sit-ins, protests, and dharnas, often with her infant children by her side.

Now, Seema says she has learned of at least six FIRs registered against her since 2022, and she fears there may be more that have yet to surface. Like many others, the fight for her brother’s return has turned into a battle to defend herself.

The pattern repeats in Kharan, Balochistan, where Zarmeena, whose husband Najeeb disappeared in 2021, now faces an FIR for protesting in her hometown. Like others, she stood in public only to demand her loved one’s return and was criminalised for it.

Similarly, Hakmeen, also from Kharan, has been hit with multiple FIRs for protesting the disappearance of her brother, Raheem-ul-Din, missing since 2016. Zarmeena has four FIRs against her. Hakmeen has three. Their search for justice has left them entangled in legal battles of their own.

According to Aisha Masood, project coordinator and campaigner with Defence of Human Rights Pakistan, the situation in Balochistan reflects a systematic effort to suppress victims and human rights defenders. “All their avenues are being blocked,” she said. “We have seen how Sammi, when she was just a child, marched to Islamabad for her father’s recovery. Since then, she has waged a long struggle not only for her own father but also for other disappeared persons. And what has this struggle given her? It has brought her numerous FIRs, harassment, and other forms of persecution — everything except the return of her father.”

On the failure of legal remedies, Aisha noted: “As far as the Commission of Inquiry is concerned, which forms JITs and then families present themselves before it, this commission has been around since 2010. That means it’s been 15 years of a government body that has failed to deliver justice to victims.” She added that the Commission has instead exploited victims, subjecting families to mistreatment and victim-blaming. “Families who come to seek justice are mistreated. They are questioned in ways that suggest their loved ones must have committed some crime, and that’s why they were taken. This kind of victim-blaming does not happen anywhere else in the world — it happens only in Pakistan. Here, those who come to seek justice are the ones interrogated. FIRs are lodged against them instead.”

When someone disappears in Balochistan, their family’s first instinct is to follow the law: to file reports, seek court orders, and appear before commissions. But what begins as a search for justice often becomes a long, exhausting process. Families wait for months or years, and when that waiting brings no answers, many turn to peaceful protest as their last remaining hope.

Yet these protests often lead to new ordeals. Families demanding the return of their loved ones face baton charges, arrests, and legal harassment. FIRs are lodged against those who speak out. Many victim families, particularly women, are left fighting legal battles of their own, rather than finding the truth about their missing relatives. The same legal system they turned to for help is used against them.

According to Sammi Deen Mohammad, who has spent more than sixteen years seeking the safe return of her father, these actions are not accidental. “The aim is clear: to silence us, to stop us from speaking out, to make sure enforced disappearances aren’t challenged publicly,” she said. “When they entangle us in court cases, FIRs, and legal harassment, it’s not just to punish us, it’s to make sure fewer voices are left to demand answers.”

Sammi insists that families like hers are not seeking confrontation. “All we want is justice, accountability, and the return of our loved ones. But how can anyone expect us to stay silent when our fathers, brothers, and sons are taken? Staying silent goes against human nature itself.”

Hazaran is a Balochistan-based journalist and researcher with a background in English Literature. Her work focuses on the lived experiences of the Baloch people and their socio-political struggles in Pakistan.

All image credits: Hazaran Rahim Dad

Member discussion