Monsoon Brides in the Climate Crisis

Names have been changed to protect the identity of people*

I’m 25 and can’t imagine marrying yet. When I read about girls younger than my teenage cousins being sent off as brides in Pakistan’s flood-hit Sindh, I can’t help but think of how survival turns into a transaction. In districts like Dadu and Khairpur, families struggling to rebuild after repeated monsoon floods often see early marriage as a way to reduce the number of mouths to feed.

I keep wondering what must go through a father’s mind at that moment, when he decides that marrying his daughter is the only way out. Is it guilt, fear, or just exhaustion from hunger? For families who have watched their homes drown twice in one lifetime, choice stops being a luxury.

Rameen* was only 14 when her father decided to marry her off. Their home was washed away during the 2022 floods, and for months, her family of seven lived in a makeshift tent near the Indus Highway. When food ran short, her father said yes to a proposal from a distant relative. The groom was in his 30s.

“He said he couldn’t feed us all,” Rameen recalls quietly, sitting on a charpai (woven bed) outside what remains of her home. “He told me it was better this way, that my husband would take care of me.”

In Sindh’s flood-affected belt, such stories have become common. As the waters recede, poverty and displacement linger, pushing families toward desperate decisions. Marrying off young daughters becomes both a coping mechanism and a way to gain social security in a time of uncertainty.

When NGOs visit these villages, they often find young brides holding infants instead of schoolbooks. Teachers who once taught them say they notice the empty desks first. The dropouts happen quietly, one by one. Some girls are married off; others are moved to relatives’ homes and never return.

According to local organisations, child marriage cases in rural Sindh have risen sharply since the floods. While there is no consolidated national data, community workers estimate that in villages like Rajo Dero and Mehar, at least one in four girls is now married before the age of 16. The pattern is especially visible in areas where livelihoods depend on agriculture, which the floods have repeatedly destroyed.

“We are seeing an alarming increase,” says Mashooque Birhmani, executive director of Sujag Sansar, a Dadu-based non-governmental organisation that works on gender rights and rural education. “Families are pushed to the edge. When a disaster strikes, they think marrying their daughters is the safest option, because it means one less mouth to feed and one less body to shelter.”

He explains that this pattern repeats every few years. Floods or droughts hit, crops fail, homes are lost, and girls become the first form of compromise. “What’s most worrying,” Birhmani adds, “is how normalised this has become. People justify it as protection for the girl, when in reality it’s a loss of childhood.”

When poverty meets patriarchy

Rameen’s mother had objected initially, but she was silenced by her husband’s reasoning. The family’s livestock had drowned, their fields were gone, and relief aid was inconsistent. “He said who will marry her later if she stays here like this,” her mother says, referring to the displacement camp. “People talk, they question our honor. We didn’t want her reputation ruined.”

In many of these rural communities, patriarchy blends with poverty. Marriage, even at a young age, is seen as security. A girl at home without a husband is seen as a burden or a threat to family honor. In crisis situations, this thinking becomes even stronger.

It’s not just an economic decision. It’s social survival; families fear gossip, shame, and being labeled careless with their daughters. So they make what they believe is the most respectable choice.

For Ayesha*, who was married at 17, the trauma followed her into adulthood. Now 20, she lives in Khairpur and is a mother of two. She was still in school when her father arranged her marriage. “He said it was better to marry now,” she says. “Our house had been damaged, and we had no money. My husband’s family offered to repair it.”

The promise didn’t last. Within months, Ayesha’s husband stopped sending money home. She was pulled out of school, pregnant soon after, and by 19, she had already suffered two miscarriages. Doctors told her that her body wasn’t ready for childbirth. “I didn’t even know what pregnancy meant when it happened,” she says. “No one told me anything. They only said it was my duty.”

Ayesha says she often dreams about her old classroom. “I still remember the smell of chalk,” she says. “Sometimes when I sweep the floor, I imagine the teacher calling my name for attendance. Then I remember where I am.”

The law and the loopholes

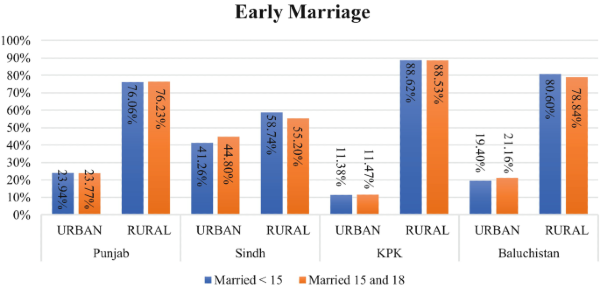

Child marriage in Pakistan is officially illegal, but enforcement remains weak. Under the Sindh Child Marriage Restraint Act of 2013, marrying anyone under 18 is a punishable offence, carrying up to three years of rigorous imprisonment (Dawn, 2014). However, across the rest of Pakistan, the legal age for girls is still 16, while for boys it is 18 — a discrepancy that continues to create confusion and legal loopholes (National Commission on the Rights of the Child, 2025). Religious clerics often resist reform, arguing that puberty marks the beginning of adulthood. In 2020, the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII) declared Sindh’s law “un-Islamic,” contending that Islam permits marriage after puberty (Dawn, 2014).

Birhmani says that local authorities rarely intervene, even when activists file complaints. “In small towns, the police don’t want to challenge the community. They say it’s a ‘family matter,’” he explains. “Sometimes, they even pressure us to withdraw the cases. We’ve had families threaten us for interfering.” Such reluctance by law enforcement echoes broader findings that police often dismiss child marriage cases as private family issues, contributing to widespread under-reporting (Dawn, 2015).

Without consistent law enforcement or social protection, the burden falls on NGOs and community workers who are already under-resourced. Many of them say they face hostility from local landlords and religious leaders who accuse them of “destroying traditions”, a reality reflected in the low number of prosecutions despite hundreds of reported cases under the Sindh law (Dawn, 2024).

The debate over raising Pakistan’s legal marriage age has gained renewed momentum in 2025. Earlier this year, President Asif Ali Zardari signed the Islamabad Capital Territory Child Marriage Restraint Bill 2025, officially setting 18 years as the minimum marriage age for both boys and girls within the capital (The News, 2025). The move was widely supported by the Women’s Parliamentary Caucus and the Committee on Gender Mainstreaming, both of which urged provinces to adopt a uniform legal age nationwide (Business Recorder, 2025). However, Pakistan’s provinces remain divided on the issue. Sindh already enforces the Sindh Child Marriage Restraint Act 2013, which sets the minimum age at 18 for both sexes (UNFPA Pakistan), while Punjab still allows girls to marry at 16 under existing legislation (NCRC Report, 2025). Efforts to raise the age in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan have stalled, with bills currently under review by the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII) (Dawn, 2025).

The CII has repeatedly deemed setting a fixed age of 18 as “un-Islamic,” arguing that puberty, not age, marks adulthood (LOC Global Legal Monitor, 2025). Conservative groups, including Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (Fazl), have also condemned the ICT law and announced nationwide protests, calling it an infringement on religious and cultural traditions (The Nation, 2025). Despite this backlash, rights organisations and legal experts continue to describe standardising the marriage age at 18 as a “human rights imperative” (Pakistan Gender News, 2025).

Under the new ICT law, Nikah registrars who solemnise underage marriages can face up to one year in prison and fines of Rs 100,000, while adult men marrying underage girls can face up to three years of rigorous imprisonment (Morning Star News, 2025).

The legislation also mandates CNIC verification to prevent falsified age claims—a step advocates hope will strengthen enforcement and help set a national precedent for protecting children across Pakistan.

A cycle that doesn’t end

Shahida*, now 30, remembers that pressure well. She was married at 15, also in Sindh’s interior. Her husband was 12 years older. “When I said I wanted to study, my father laughed,” she recalls. “He said floods come and go, but a husband stays.”

The marriage lasted, but happiness never did. Her husband forbade her from working or visiting her family. She describes her youth as “a long, silent punishment.”

Even now, she flinches at the sound of heavy rain.

“When the monsoon comes, I still feel that fear,” she says. “It reminds me of when my father said the water would take everything, and that I should be grateful for being chosen by someone.”

Sometimes, she watches her own daughter, now nine, and wonders what her future holds. “I tell her every day that she will study,” Shahida says. “But when it rains, I start praying again. Because I know what floods can take from you.”

The emotional toll

Psychologists say these experiences often leave deep emotional scars. “Child brides are forced to perform adult roles before their minds are ready,” explains Dr Madiha, a Karachi-based therapist who has worked with survivors of early marriage. “They are deprived of autonomy, exposed to sexual trauma, and conditioned to suppress their own pain.”

Dr. Ali, a psychologist based in Washington DC, adds that climate change has added a new dimension to gender-based violence in rural Pakistan. “When you have repeated disasters and no safety nets, girls become the first to pay the price. The crisis is economic, but the impact is psychological.”

She says many of the women she counsels struggle with anxiety, nightmares, and depression, but rarely name it as such. “They say they’re tired, or that their heart feels heavy. The language for trauma doesn’t exist for them.”

Climate disasters, gendered consequences

Pakistan ranks among the countries most vulnerable to climate change. Each monsoon season brings new waves of displacement. In 2022, record-breaking floods affected more than 33 million people, submerging one-third of the country (Britannica, 2022). Sindh was the hardest hit, with around 7.9 million people displaced from their homes (UNHCR, 2022). Even three years later, many families still live in makeshift shelters or half-rebuilt homes as recovery efforts continue at a sluggish pace (Britannica, 2022).

The losses ripple across generations. Parents who once relied on farming now depend on daily wage labor or relief handouts. In these conditions, daughters’ futures are often negotiated through marriage rather than education.

And yet, every year, families hope the rains will be kinder. They plant again, rebuild again, and believe the next season will be different. But when the clouds darken, that hope starts to fade. “We know what’s coming,” says Birhmani. “We just don’t know who we’ll lose this time.”

Small resistances

Sujag Sansar and similar NGOs have been trying to change that narrative. They hold awareness sessions in villages, teach families about the risks of child marriage, and provide schooling support for girls.

“It’s slow, difficult work,” Birhmani admits. “You can’t just tell people not to marry their daughters. You have to show them alternatives, income opportunities, education, and social safety. Without that, change won’t come.”

He shares a story of one family that decided to delay their daughter’s marriage after attending the NGO’s sessions. The father was initially resistant but later agreed to let her finish school. “He said, ‘I never thought a girl could also earn,’” Birhmani recalls. “That’s the shift we need, from seeing girls as dependents to seeing them as individuals.”

Still, such cases remain rare. In most of Sindh’s flood-prone areas, girls’ futures continue to be decided by circumstance. For Rameen, marriage has meant a new kind of confinement. Her husband works in another village, and she spends most of her days fetching water and caring for his younger siblings. She hasn’t seen her parents in months.

“I thought I’d go back after a few weeks,” she says, her voice soft. “But he says wives stay with their husbands.”

Her childhood has been replaced by chores and expectations. “Sometimes I dream of school,” she says, eyes fixed on the dusty road ahead. “I remember writing my name on the blackboard. I don’t know if I still can.”

The quiet aftermath

Across these villages, resilience takes quiet forms. Mothers push their remaining daughters to keep studying, even when schools are miles away. Some girls hide their books under bedding so that no one finds out they still read. Teachers run informal classes in tents, teaching whoever shows up. In a place where everything can be washed away overnight, education becomes an act of defiance.

Yet progress feels fragile. The floods that once came every few years now return almost every monsoon. Each time, the community starts over, new shelters, new debts, new losses. And each time, more girls disappear into early marriages that promise safety but deliver silence.

When I spoke to Birhmani again recently, he said their team was preparing for the next monsoon season. “We know what’s coming,” he sighed. “People will be displaced again, and the same stories will repeat. Unless there’s long-term planning, these girls will keep being sacrificed to survival.”

I think about that word, survival, and what it really means for those girls. To survive shouldn’t mean to vanish into adulthood before you’re ready. It shouldn’t mean losing your name, your books, your chance to grow.

When people talk about the floods, they mention statistics, millions displaced, homes destroyed, and crops gone. But behind those numbers are girls like Rameen and Ayesha, whose childhoods were bartered for the illusion of stability. They are the unseen cost of a climate crisis that keeps demanding human trade-offs in the poorest corners of the country.

Pakistan’s monsoon brides are not symbols of resilience. They are reminders of what we continue to lose when poverty, patriarchy, and disaster intersect. In a country where girls are taught to endure rather than dream, their stories ask a harder question, how many more childhoods must be sacrificed before survival stops being mistaken for safety?

Aleezeh Fatima is a pharmacist-turned-journalist based in Karachi. Her work focuses on climate, displacement, migration, health, and human rights. When she’s not reporting, she’s either hoarding books and jhumkas, indulging in sappy sitcoms, or sharing a laugh with friends at a coffee shop. She tweets at @dalchawalorrone.

Member discussion