Pakistani Women Turn To AI Amid Mental Health Taboos

For many women in Pakistan, speaking about mental health remains fraught with difficulty. Therapy exists, yet seeking it out is often felt taboo. Conversations about emotional struggles, anxiety, or depression are frequently hidden behind closed doors due to social stigma, family pressures, and fear of judgment.

In some communities, simply admitting to struggles with mental health can invite gossip, shame, or a perception of failing in her responsibilities as a woman.

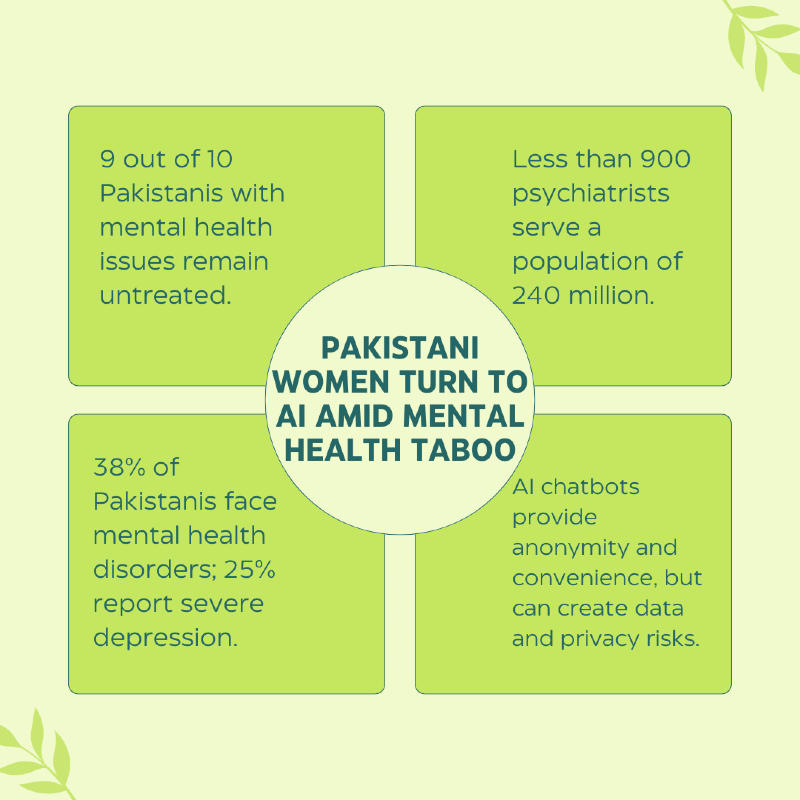

Due to these circumstances, serious cases of mental health are increasing among women, including anxiety, depressive disorders, and stress. Although awareness programs are taking place along with a few reforms in this matter, a gap is being filled by AI chatbots and emotional support apps in a subtle manner.

The appeal lies in AI’s anonymity, accessibility, and nonjudgmental nature, offering a space for women to express feelings they otherwise cannot share.

However, despite their capabilities, these tools also have hidden weaknesses. Experts warn that personal information shared with AI systems could be exploited, increasing women’s susceptibility to Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence (TFGBV), a growing concern in Pakistan and across South Asia (UNFPA).

Beyond the risk of misuse for malicious purposes, such as using data breach or machine learning algorithms, AI can widen existing disparities by incorporating biases and discrimination.

Additionally, AI presents other moral and ecological challenges, such as high energy consumption, making it pivotal to proceed with the development of moral AI production and utilization.

For Rabail, a 23-year-old university student, talking about her feelings has always been a challenge.

“I feel like I don't have anyone to whom I can talk about my feelings,” she said. She turned to AI tools like ChatGPT, where she not only used it for studies but could speak anonymously at any hour.

“Sometimes you just need someone to listen, and AI felt easier than talking to people,” Rabail said. Her late-night chats often focus on work stress, studies, or relationship pressures, subjects she finds difficult to talk to with friends.

She describes the support as somewhat helpful because AI cannot fully understand emotional context, read tone or body language, or offer genuine empathy. Its responses can feel generic or repetitive, and it cannot provide real reassurance, accountability, or crisis support, making it a limited substitute for human connection.

“Women are using AI chatbots because they need a space where no one will judge them. They are scared to open up to real people,” explained Bisma Shakeel, an MBBS doctor, influencer, and mental health advocate. Bisma added that many women perceive AI as a safe, private alternative. “Chatbots feel safe because they are private, but people don’t realize how much of their data is being fed, stored, and used,” she warned.

Understanding TFGBV and its link to AI use

Thus, fear of TFGBV also shapes the ways in which women seek emotional support online. This includes the misuse of technology for harassment, harm, or control of the target of this violence, more often than not, a woman. It may include online harassment, non-consensual intimate image sharing, cyberstalking, and the misuse of personal data.

It is because of these threats that so many women do not feel safe sharing on social media or with people online. Thus, it pushes them toward chatbots and emotional support apps powered by AI, an apparently safer, private space where they feel free to share their feelings without judgment, exposure, or harassment.

Samana Butul, Delivery Associate of Gender and Child Security Portfolio at Legal Aid Society, said, “When you talk about tech-facilitated gender-based violence, technology can be a source of harm for women. Women are more vulnerable to online violence than men.”

Regional studies by the UNFPA and the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) indicate that TFGBV is on the rise in South Asia, underscoring the risks women face when gendered vulnerabilities intersect with digital spaces.

These risks include online harassment, stalking, non-consensual sharing of personal or intimate content, identity theft, and misuse of private data, which can have both online and offline consequences.

In Pakistan, formal support systems remain limited, and AI chatbots provide emotional relief but may expose sensitive information to misuse. “Mainstream chatbots such as ChatGPT have largely been open about the fact that chat logs are not only saved but also used to train AI algorithms,” noted the Digital Rights Foundation (DRF) research team. “One of the largest risks of chatbots storing conversations, not only sensitive emotional ones, is the likelihood of data breaches and hacking that can make anyone privy to the information being shared,” she added.

The mental health landscape and treatment gaps

According to an article by The News, recent data estimates that 38% of Pakistanis suffer from some form of mental health disorder, with approximately 25% experiencing severe depression. During a global conference on Brain and Mental Health hosted by the Agha Khan University (AKU) highlighted that mental health services remain severely under-resourced, with roughly one psychiatrist for every 500,000 people, failing to meet demand for a population of over 240 million.

Consequently, Sehtyab, an online mental health clinic, highlighted that more than 90% of people with common mental disorders remain untreated.

Social stigma, cultural conservatism, and gendered expectations often suppress emotional expression, particularly among women. Barriers include shortages of female therapists, concerns over confidentiality, and economic limitations. Female therapists are especially important as gender norms make it difficult for women to open up to male professionals.

For Sanam, a 26-year-old professional, growing loneliness pushed her toward AI. She uses apps such as Woebot, Replika, and Gemini. “Sometimes you just need someone who won't judge you,” she said.

“Digital platforms can be a safe haven for women, but they can also be a trap,” said Samana. “Some friends share so much with AI chatbots that they refrain from sharing things with us. They become more isolated, more confined, which is not good.”

Sanam worries about privacy. “I do think about where these conversations end up,” she said.

When asked about how safe conversations with AI chatbots are, the DRF research team added, “Information such as this can also potentially be disclosed to governments, making individuals open to a new form of surveillance that not only tracks factual information (such as location, address, conversation logs) but also behavioral aspects (who you are likely to vote for, what your problems are, what your sentiments are towards the government).”

Systemic barriers driving AI reliance

Women’s reliance on AI stems not just from personal choice but systemic failures. Deep-rooted social stigma links emotional distress to weakness. Seeking therapy may be seen as disloyalty, unstable behavior, or a threat to marriage. Insufficient mental health infrastructure leaves rural women without access to professionals or basic counseling. Access limitations, high costs, and cultural restrictions further compound the issue.

Labour and gendered roles exacerbate this burden. Women are often expected to carry emotional responsibilities for entire households. As Bisma observed, “Even if a child errs, the responsibility somehow lands on the mother; this is the nature of patriarchy.” Women are expected to manage stress privately and avoid “weighing down” others with their emotions.

To this, DRF’s research team highlighted that, “At DRF, through our helpline and research, we unfortunately have seen cases where digital platforms are exploited to harm women in ways that can have offline consequences.”

In such an environment, AI chatbots offer discretion, affordability, and convenience, but convenience does not eliminate risk.

AI chatbots: promise and pitfalls

Global research indicates AI emotional support can temporarily reduce stress, but cannot replace therapy. A 2025 review in Frontiers in Psychiatry noted that chatbots improve short-term well-being but cannot substitute human-led interventions.

“Constant reliance on a bot stops you from building resilience. Resilience only grows when you face real-life situations,” warned Bisma. “There have already been cases where AI bots encouraged harmful behavior, even suicide, which shows how dangerous this reliance can become.”

AI cannot interpret tone, body language, or emotional cues. “AI validates everything you say, even when you're wrong; that creates an unrealistic fantasy of what relationships should look like,” Bisma noted.

Experts emphasize that digital companions should augment, not replace, human support. Solutions include AI literacy to understand privacy risks, stronger AI regulation, and expanded female-friendly mental health services.

“If I could give one warning to women using AI, it would be this: it’s not genuine. Don’t believe it straightforwardly. Don’t expect AI to understand you,” said Samana. “It cannot replace the love, warmth, and trust you get from real people. Sometimes, it can even give harmful suggestions (like self-harm prompts) that are not good for you.”

Some real-life cases show how AI can be risky. For example, in a recent case that happened this year in the US, a teenage boy interacting with a chatbot received harmful messages, including suggestions of suicide, which tragically contributed to his death. This shows how AI can affect vulnerable users if not used carefully.

For women like Rabail and Sanam, AI chatbots are quiet companions in a society where mental health discussions are constrained. Yet without safeguards, these tools can become channels of exploitation rather than support. They provide a fragile bridge between invisibility and voice, a way to vent, reflect, and survive emotionally, but the specter of TFGBV, data exploitation, and emotional dependency remains.

AI in mental health should be treated as a patch, not a fix. Women in Pakistan need safe spaces, not only in apps but in homes and communities. Awareness, regulation, and structural reform are essential to ensure emotional support empowers rather than endangers. Until then, every late-night conversation with a chatbot remains a quiet act of resistance, a search for relief, dignity, and a voice that asserts: “I matter.”

Pareesa Afreen is a Karachi-based journalist and sub-editor at Geo News, currently working with The Jang Group’s digital platform, Gadinsider, where she covers technology and business stories. Her work also appears across other outlets, focusing on digital rights, climate change, and social impact.

Member discussion