The Heavy Climate Burden On Women - Why Climate Change Isn’t Gender Neutral

Some names have been changed to protect privacy

Behind every flood toll in Pakistan lies a woman’s untold struggle, and when it pours, women are sometimes left alone to fend for themselves and survive.

Many women in the recent floods in Karachi witnessed nothing short of terrifying events, including being trapped in the rain with nowhere to turn. Among those trapped was Sara*, a biochemist working in a pharmaceutical company on the city’s outskirts. Her workplace is more than an hour's drive from her home, and she relies on office-arranged transport for her daily commute.

Early warnings had already been issued that day. Many workplaces acted responsibly, allowing employees to leave early in order to avoid looming disaster. But some offices ignored the forecast and insisted that staff work until 4 pm. By then, the entire city was submerged, roads were blocked, and transport was immobile. Instead of providing a safe space to wait, Sara’s workplace management told the employees to ‘manage on their own’.

Left stranded, many working women across the city waited in vain for the water to recede. As night fell, they had no choice but to begin walking home. Guided by male colleagues, these same women navigated streets where manholes and open drains were invisible beneath floodwaters. They walked for eight hours through sewage-contaminated water with constant risk of electrocution or falling into open holes – dangers tragically common in Karachi.

Sara described it as a near-death experience and one of the most helpless moments of her life, which left her deeply traumatized. She pointed out that the fact that this occurred in Pakistan’s largest city – the economic backbone of the country- underscores not only the fragility of its urban infrastructure but also the disproportionate risks that disasters pose to women.

The experiences of Sara and countless women like her in this situation reinforce a haunting reality: women in both urban and rural flood-affected areas across the country are facing horrors daily, from life-threatening journeys to heightened exposure to waterborne diseases.

The only question that arises now is, when governments fail to provide even the basics – functional drainage, water storage, sewage systems, and safe, walkable roads in the urban and rural areas of the country, how can citizens expect to adopt modern solutions to the climate crisis? Without these essentials, women are left with a constant risk of losing their lives, livelihoods, and access to basic facilities.

“Unless we establish proper planning mechanisms to manage the overpopulation of cities, which is the root cause of the uncontrolled urbanization we see today, there can be no meaningful change. Any attempts will remain merely cosmetic. Until we address these root causes, such problems will continue to persist for years to come,” says Urban Planner & Sustainability Expert, Farhan Anwar, who is an active member of Shehri-CBE (Citizens for a Better Environment), Founder of Urban Collaborative, and currently serving as Associate Professor at Habib University.

Lahore, one of the country’s other major metropolitan cities, is often considered relatively developed, with access to public transport and robust infrastructure. Yet, the recent floods revealed how far it is from being ‘gender neutral’ , or a place where women would be able to navigate climate disasters with the same level of access to resources or safety as their male counterparts. Urban flooding has affected women and children in ways that one can’t even think of.

Working women who rely on public transport for their daily commute find themselves stranded when the city floods, as services that claim to be readily available often disappear when needed most, affecting both their mobility and safety. For women in rural settings, the burden is even heavier. They hold the primary responsibility of securing food, water, and fuel for their families, tasks that increase their workload by becoming more time-consuming and physically demanding. Rain pouring down their roofs, contaminated water supplies, poor sanitation, and frequent power and gas outages put them at a greater risk during these unsafe conditions.

“In many places, employers consider it a business responsibility to provide safe and quality transport, particularly for female employees. While no law mandates this, offering secure transportation has increasingly become a standard part of the modern workplace,” says Zeenia Shaukat, who currently serves as the Director of The Knowledge Forum

For many working women in Lahore, these challenges became more than mere statistics when urban flooding made reaching their workplaces an everyday struggle. Women who rely on ride-hailing apps for their daily commute often find themselves stranded for hours during rainfall, as rides disappear from the map. In Lahore, when monsoon rains started flooding the streets in the city, the downpour was relentless, and roads were submerged. It was impossible to reach on time until the water level receded. After waiting for over an hour, Saba finally managed to book an auto rickshaw since cars were unavailable, and delaying further wasn’t an option as urgent tasks were due. But midway, the water rose inside the rickshaw, leaving it stranded in the middle of the road and forcing her to turn back home.

For her, this experience underscored the urgent need for climate-resilient workplace policies. When extreme weather events disrupt mobility, especially for women relying on public or ride-hailing transport, there should be flexibility – whether in the form of remote work, relaxed reporting times, or safe transport arrangements. Above all, safety must come before attendance. Unfortunately, in Pakistan, employees are often expected to show up on time even in the face of natural disasters. Health and safety continue to be pushed under the rug, even as climate change increasingly disrupts our daily lives.

“Our current labor laws are not aligned with the challenges of climate change. Moreover, different laws regulate different workplaces. Factories, banks, mining, and retail sectors all operate under separate frameworks. Health, safety, and environmental laws require companies to prioritize employee safety and workplace conditions. However, there is still a pressing need to integrate climate-related safety regulations. In many places, even basic ventilation is lacking, though the labor department conducts factory inspections and penalizes non-compliance,” Shaukat says.

According to the UN News Report (2022), climate-related disasters force girls to drop out of school and increase the risk of violence and exploitation for displaced women, limiting their opportunities and increasing their vulnerability. In 2022, catastrophic floods killed 1700 people and displaced over 33 million, DAWN reported. Exposure to floodwaters mixed with sewage and dirt puts them at high risk of deadly waterborne diseases. The children and women living in these conditions, without proper shelter, food, or healthcare, are left at the mercy of relief work and government support.

Beyond economic struggles, climate disasters create security concerns. The rule of law often seems to serve only the privileged and, more often than not, fails to even acknowledge the everyday struggles of the underprivileged. During floods and other emergencies, already strained community services such as policing and law enforcement leave women more exposed to heightened risks of sexual and domestic violence.

In underdeveloped areas, women and girls have far less access to climate information, early warnings, seasonal forecasts, mobile technology, and financial credit. Gendered roles, ranging from who makes household decisions to who controls access to resources, further shape how climate change impacts women and men differently. According to DAWN, globally, women and children are 14 times more likely to die in climate-related disasters, and 80% of those displaced by climate change are women.

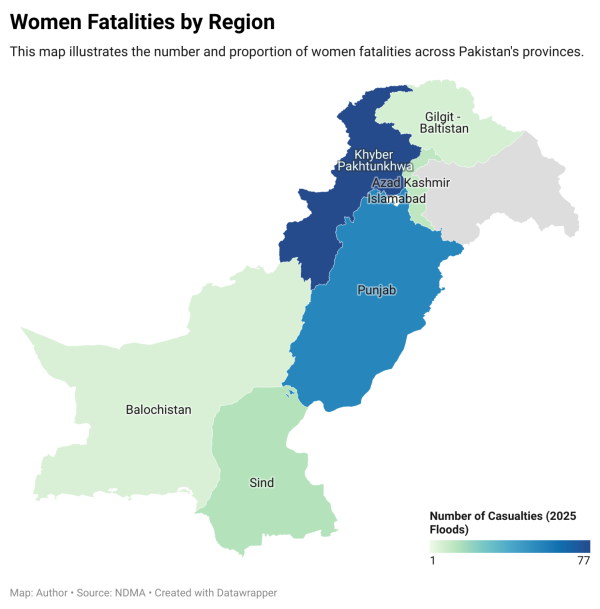

The floods of 2025 further aggravated existing inequalities to an alarming level, as the available funds and aid supplies were not properly utilized due to both administrative bottlenecks and the lack of an accountability mechanism. Displaced pregnant women are among the most affected, struggling to find safe shelter, basic hygiene, and privacy. The unavailability of medicines, sanitary pads, maternal kits, and doctors puts them at enormous risk of catching infectious and water-borne diseases, leaving them in life-or-death situations. There are no safe and separate washrooms for them, and most have to rely on nearby homes’ facilities, which are also used by men.

Disasters like floods don’t just end with the water receding. There is an entirely different challenge to be dealt with, the “post-flood effects”. A study reveals that 75% of women in Pakistan are highly vulnerable and marginalized, often experiencing elevated maternal mortality rates during floods. Additionally, women endure harsh conditions in camps, shouldering a greater burden than men in the face of natural disasters. Consequently, this takes a toll on their mental health, making them more susceptible to psychological issues. As a result, women emerge as the most vulnerable group, grappling with uncertainty during and after floods. The disaster recovery process depends on multiple factors, including the severity and nature of the catastrophe, and community or individual efforts often fall short of fully restoring what has been lost. In Pakistan, however, mental health still remains a taboo topic, and women, who are already coping with immense material losses, are left to suffer in silence when it comes to their mental well-being.

It’s clear that NGO efforts and civil society stepping in are not enough.

“Many departments now lack basic data such as population figures or the number of workers in a given area or factory. This makes the situation highly complex. While organizations can raise their voices, conduct research, and maintain dialogue with the government, it ultimately remains the state’s responsibility to take concrete actions, protect workers’ rights, and engage political leadership to implement meaningful reforms,” Shaukat says.

Climate projections suggest that by 2040, nearly 5 million more people in Pakistan will be living in flood-exposed areas (World Bank, 2024). This rising vulnerability is not only a consequence of shifting climate patterns but also of rapid, unplanned urbanization. Cities such as Karachi, Lahore, and Rawalpindi have expanded rapidly, with informal settlements often emerging on or near natural floodplains. These densely populated communities are typically low-income and lack resilient housing, drainage systems, and access to emergency services. Consequently, when floods occur, they endure the greatest displacement and economic losses. The 2022 mega floods, which affected 33 million people across the country, including large populations in urban centers, underscore the magnitude of this growing urban vulnerability.

Pakistan’s vulnerability to extreme weather events means that any recovery efforts are constantly at risk of being undone by the recurring floods, making sustained rebuilding a long-term challenge. According to The Express Tribune, over 829 illegal encroachments have been recorded on rivers, streams, and natural water channels across Punjab, obstructing water flow and intensifying the risk of urban flooding. The Multan Zone reported the highest number of encroachments (676), followed by Sahiwal, Bahawalpur, and DG Khan divisions (153 combined). Urban planning expert Sani Zahra attributed recurrent flooding in major cities to outdated and insufficient sewerage systems – more than 40% of Lahore’s drainage lines are blocked or inadequate, with several overtaken by illegal construction.

Environmentalist Dr. Zulfiqar Ali added that climate change has intensified monsoon patterns, as rising temperatures increase atmospheric moisture and accelerate glacial melt, triggering flash floods.

In Karachi, inadequate urban planning and underdeveloped drainage networks have worsened flood impacts, inundating residential and commercial areas. North Karachi remains particularly vulnerable due to its proximity to the Lyari River and Gujjar Nala.

Reconstruction is a multi-year process, and the recent flooding patterns have made it quite obvious that we need climate-resilient, evidence-based solutions for the sustainable development of both urban and rural areas. So that being hit by a disaster like flooding should not become the “new norm” that we simply learn to endure under the guise of climate change.

These solutions include allowing water reservoirs to follow their natural course according to the region’s geography, designing rainwater management systems that take into account the specific vulnerabilities of each area, and prioritizing localized water security measures such as building wells in rural areas, rather than diverting rivers and streams through the construction of dams; interventions that often increase flooding risks in nearby communities. Most importantly, Pakistan must invest in installing early warning systems for rural areas where internet connectivity is limited and social media alerts are often inaccessible, leaving people dangerously unprepared.

What Pakistan urgently needs is a paradigm shift: to step ahead and rethink what sustainable development should look like in the age of climatic disasters, instead of proposing 20th-century solutions for 21st-century record-breaking disasters like the 2025 floods.

There’s so much that still needs to be addressed if we are to build truly just climate-resilient solutions. Ones that offer a move away from patriarchal structures and women’s limited participation. After all, when women are sidelined from the very forums that decide their future, inequality begins there. Above all, only women understand their own needs and requirements; no one else can determine what should be done for them. It is high time that women of Pakistan take decision-making into their own hands, and they must not be deprived of this basic right. The untapped potential of women as leaders in building community resilience, as well as advocates in leadership and decision-making structures, must be recognized at all levels.

Saba Tariq is a Lahore-based Environmental Scientist and Climate Activist, currently leading her project on Climate Education and Awareness with the Global Shapers Community, World Economic Forum. She can be reached out at: tariqsaba039@gmail.com.

Member discussion