The White In The Flag: Talking About Minorities In Pakistan

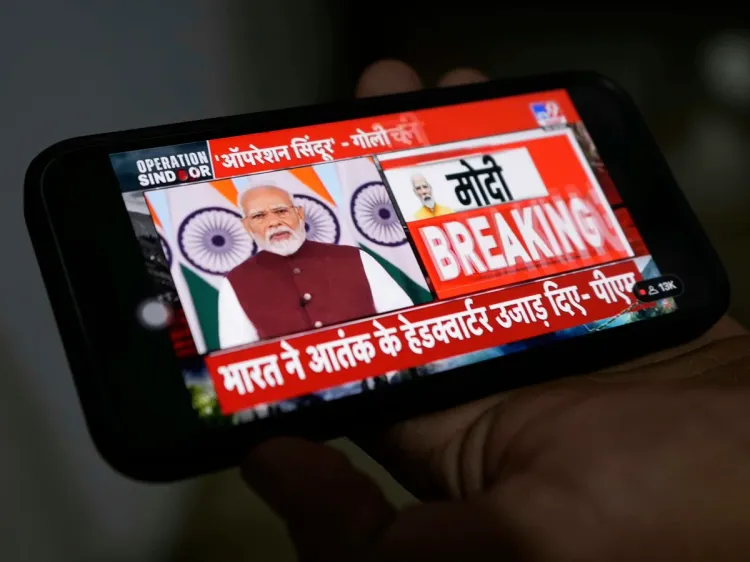

With Eid Ul Azha around the corner, authorities have appeared to crack down on the Ahmadi community once again, with the Lahore High Court barring Ahmadis from practising “Islamic Eid Rites.”

A letter written by the court to the Lahore police details that with Eid being a Muslim festival, only Muslims should perform its rites. This is the latest incident in a long history of control faced by Pakistan’s Ahmadi community, who have long been punished by authorities who deem their practice of religion to be wrong, and have through the last few decades, pushed to make all aspects of it unconstitutional. These policy level decisions feed into societal mindsets, turning it into a vicious cycle that continues to circle around - one feeding into the other.

Violence against the Ahmadi community also resulted in the death of 71 year old Tahir Mahmood earlier this month, who died in police custody after alleged mistreatment. This isn’t even the first time this year that the Ahmadi community has been attacked, yet nothing seems to change. Despite citizen led initiatives to document instances of hate speech, there’s been little change in policy. And while activists have been calling for change for ages, there seems to be little impact.

Part of that could be the way we talk about these incidents. When speaking to Polis Project, an advocate from the Ahmadi community pointed out that the media only talks about Ahmadis, or even other minority communities in Pakistan when they experience extreme violence or someone loses their life. What this kind of media coverage does is sensationalise minority experiences. Instead of humanising them, we paint vivid stories of the “other” that we pity, and think our sympathy is enough to justify othering them. Instead it's vital that we start featuring more minority voices within media spaces in general. Inclusion doesn’t have to be forced or superficial, it has to become part of the everyday, and we need to focus on the people working to make that a reality.

Why “Minority Rights” Isn’t Enough

Last month a seminar titled “The Role of Minorities in the Creation and Continuity of Pakistan” was held at Alhamra Art Council, Lahore, where Provincial Minister of Minority Affairs, Ramesh Singh Arora was a chief guest.

Arora was accompanied by religious leaders from various religious communities who appreciated the efforts in highlighting minority contributions in Pakistan - but the truth is it simply isn’t enough to appreciate minority groups and think that’s enough. Different people from different religious backgrounds will have varying experiences in society and how people perceive them.

One example is when it comes to hiring domestic help, many Muslims we know are okay with hiring Christians to work in their homes but are less open to having Hindus in the same position. Meanwhile Christians, Hindus or other groups may not be ostracised for practising their religion the same way Ahmadis are because of the ways in which Ahmadi beliefs are perceived by right-wing Islamic groups.

That’s not to say one group faces more discrimination than the other necessarily, but just that it may present in different ways, and needs to be dealt with differently.

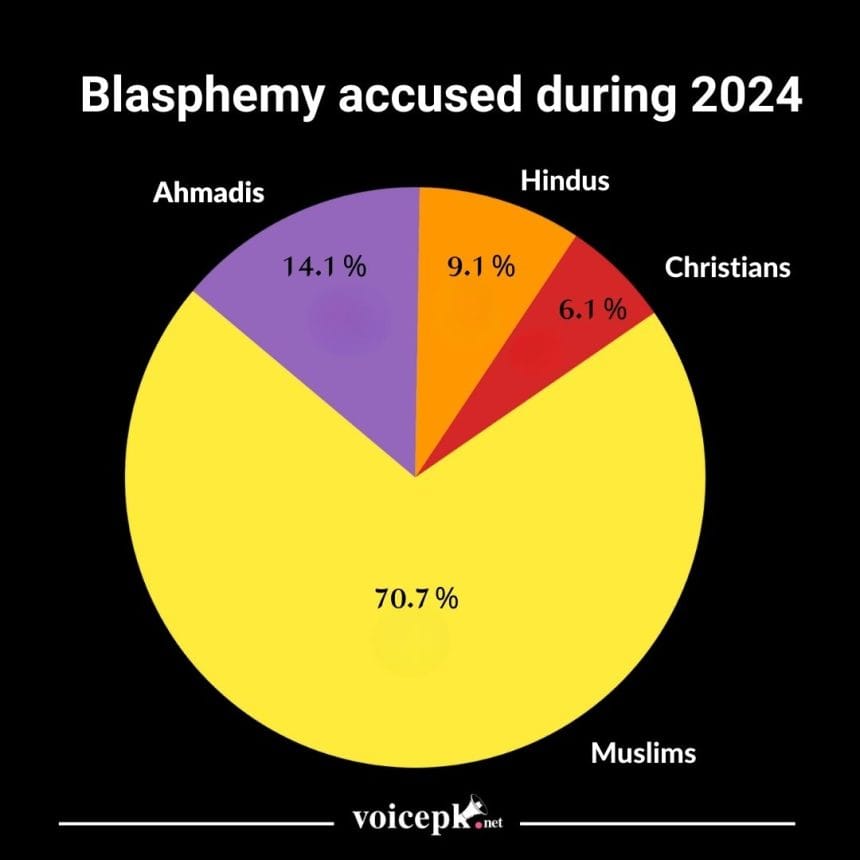

Human rights activist Jaya Jaggi, recently wrote an article on the increase in online hate faced by Hindus with digital spaces in Pakistan, detailing how there’s been an increase in blasphemy accusations, as well as disinformation and digital incitement that has very real offline consequences. These include attacks on Hindus' places of worship and forced conversions of young children, both boys and girls.

Are We Seeing Change?

In light of increasing demands by activists and rights groups to improve the treatment of minorities, Pakistan set up a commission in May that would specifically be dedicated to improving minority rights.

According to the bill, the commission established by the prime minister will consist of 13 members, including two minority members from each province — a woman and a representative of the largest minority in that province.

In an open letter written on National Minorities Day last August, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan’s National Interfaith Working Group — comprising leaders from various faith communities, as well as lawyers, journalists, and human rights defenders — demanded stronger protection for minorities.

The bill’s passage “is a significant and historical moment for Pakistan's polity and society,” said Peter Jacob, a Catholic human rights activist in the country.

“The law provides a strong basis for creating an empowered and autonomous human rights body,” said Jacob, who heads the Lahore-based rights group, Centre for Social Justice.

But government efforts will only go so far until we start bringing about a mindset shift within society, which can only be done when we create space for advocates and activists who have been talking about these issues and how to fix it. Whether it’s listening to community members about what their communities really need, or giving up space to make sure their voice gets across, support within this area can take different forms.

Voices like Jacob or Jaggi have been working tirelessly within these spaces, but they only get a voice in the mainstream when someone in power decides to do so. Otherwise their work often gets limited to their own circles.

It is this problem - of only talking about minority rights under the same umbrella or when a major violent incident happens - that we need to solve. For many people, the violence and oppression is everyday, from being called Kafir as a slur to job discrimination or children having to sit through educational content that talks down to their religion and promotes bias.

From fixing electoral inconsistencies, to what may be an upheaval of our education system, change still has a long way to go, and it starts with listening.

Member discussion