Who Wins In The India-Pakistan Media War?

A month after Pakistan and India almost went to war, it seems the situation around the Rafale jets still remains unresolved. This week, Indian media reported that Rafale Maker Dassault has said Pakistan’s claims of downing Rafale’s used by India are false. Yet, no other international media outlets have verified this.

This isn’t the first time claims around success and victory narratives are being thrown around in the media. In fact, the latest conflict played out in digital forums just as much as it did on ground, as a sharp increase in both misinformation and disinformation continued to dominate not only social media platforms, but mainstream media as well. Tactics such as AI generated deepfakes, emotionally riled up reactions and wrongly crediting news outlets were all commonly used to dominate the narrative.

From everyday citizens to journalists and factcheckers, across the two countries most people spent the days around the conflict trying to filter out the noise. Analysts and experts across the world talked about what was happening as a new dimension to war itself, where disinformation, fake news and false narratives are used to shape both local and global perceptions of what the realities were. In the India-Pakistan media war that seems to continue even now, both Indian media’s credibility and the dangers of social media in conflict have continued to become increasingly clear. While the use of social media in war has been seen increasingly since Israel’s latest assault on Gaza started in 2023, South Asia’s latest conflict added different elements into the mix.

Why Fight A Media War?

For both India and Pakistan, relations with the other side aren’t only politically complicated - they’re steeped in decades worth of emotional history. After all, even a cricket match isn’t free of emotional outbursts, so when it comes to war - a fight to control narratives is to be expected.

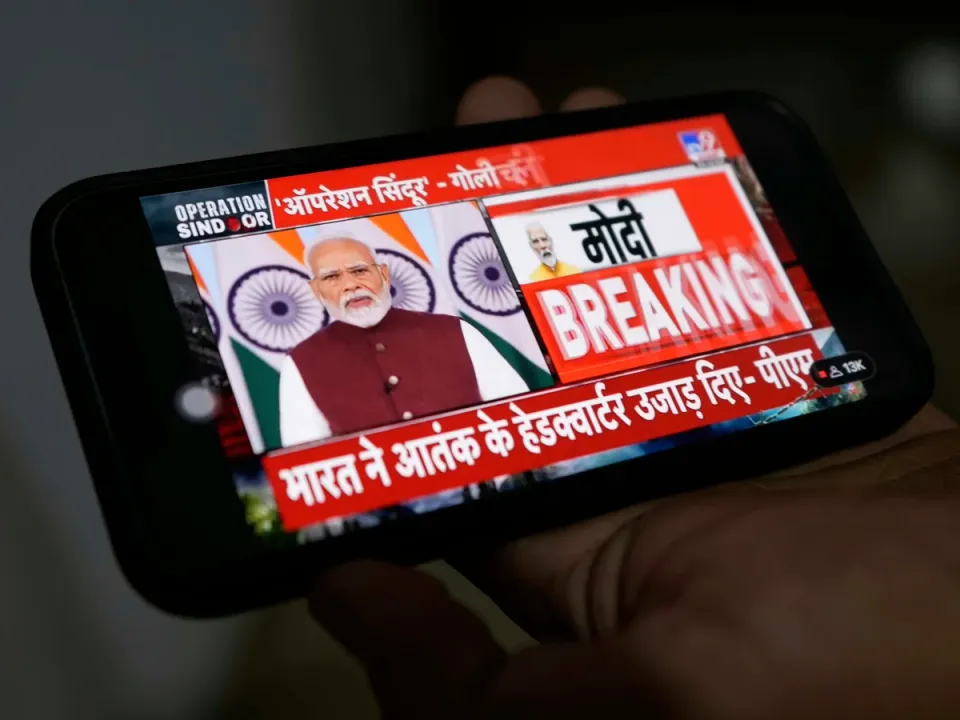

But in this globally connected world controlling the media narrative also means controlling how the world sees you, and the position it gives you on the global stage. Pakistan has long been made out to be a country that harbours “terrorists”, and that’s the narrative India pushed this time as well. India’s Operation Sindoor, which triggered the start of the recent conflict, took place in what India claimed was a response to the Pahalgam attack on 22 April, which they blamed Pakistan for. India’s claims that Pakistan funds attacks in India and Indian-occupied Kashmir aren’t new, and this probably won’t be the last time.

For Pakistan, reclaiming the narrative has been equally important in order to find new footing on the global stage. The previous narratives of Pakistan harbouring “terrorism” had led the country to previously remain on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)’s grey list. Following the Pahalgam incident, India has been pushing for the FATF to ‘grey-list’ Pakistan once again, but so far, the organisation has refused.

Speaking of the media war that has dominated the last month, journalist and factchecker Sameen Aziz, who has also worked with Soch Fact Check tells Echoes, “It’s years of pent up frustration and division that’s causing this disinformation and misinformation coming from both countries about each other. There’s misinformation about Pakistan coming from India and vice versa.”

Who Wins?

The onground conflict may be over, but experts believe the media war can continue, especially as India continues to fight to regain the narrative that Operation Sindoor was successful. Despite India’s powerful status within global politics, there seems to be a general - and surprising - consensus that Pakistan may have come out on top. While Indian citizens have called out their own media spreading disinformation, independent journalists like Sahar Habib Ghazi praised Pakistan’s official statements and reporting on what was happening in the conflict.

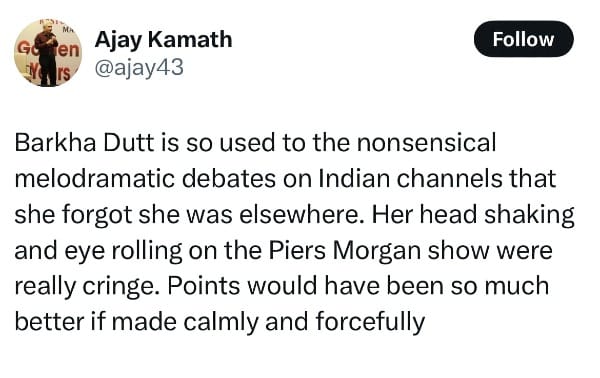

The most prominent example of the difference in Pakistani and Indian narratives was perhaps the segment on the Piers Morgan show where guests Hina Rabbani Khar, previous Minister of Foreign Affairs in Pakistan and podcast host and comedian Shehzad Ghias Sheikh were joined by Indian journalist Barkha Dutt and podcaster Ranveer Allahbadia. While Dutt and Allahbadia spent the segment making faces while the Pakistani guests spoke, the latter two came off as a lot more composed, with many Indians also calling out the Indian panelists for their behaviour.

Still disinformation was spreading from both sides. Bazigah Murad, a factchecker working at iVerify, says that her team was overwhelmed with having factcheck an unprecedented amount of content. “We were barely done fact checking one piece of news and a second one came up. We have more mis/disinformation and less fact checkers, so there’s an uneven ratio,” Murad tells Echoes while adding, “the consequence is a lack of trust, in media outlets, in media in general.

It’s not about which side was better at shaping the narrative, but about the impact these media wars leave on citizens in the long term, and when we promote disinformation no-one wins. “AI played the worst role in the India Pakistan conflict, there was AI in almost every piece of content we factchecked during this time,” Murad tells Echoes.

So even as awareness around misinformation grows, there’s still a need to find reliable sources of information.

“I think what happened after Israel & Gaza started, was that we saw a shift in public perception as they realised that the kind of reporting western media did was very whitewashed and biased. There’s been a global shift which is also happening in Pakistan. However, I still feel we need to identify outlets who are accurately reporting whether they are new or emerging, internationally and locally,” Aziz says.

She also identifies X and TikTok as the platforms with the most and fastest spreading disinformation. AI generated videos and use of older videos in false contexts can both easily mislead a larger population in South Asia - especially those who may not be able to read English.

“People are more aware of fake news and call it out, but then people also keep putting out fake information. The main thing is you have to slow down and not consume so much information at once,” says Murad.

Anmol Irfan is a freelance journalist, editor and the co-founder of Echoes Media. Her work focuses on marginalised narratives in the Global South, looking at gender, climate, tech and more. She tweets @anmolirfan22

Member discussion